Recent news of rosier revenue forecasts has triggered calls to use projected revenue surpluses to fund property tax cuts. However, basing ongoing fiscal obligations such as tax cuts or new spending on revenue projections is incredibly risky and could force future tax increases or funding cuts to vital services like Nebraska’s public schools.

Revenues fluctuate naturally, making projections a poor foundation for permanent policy changes

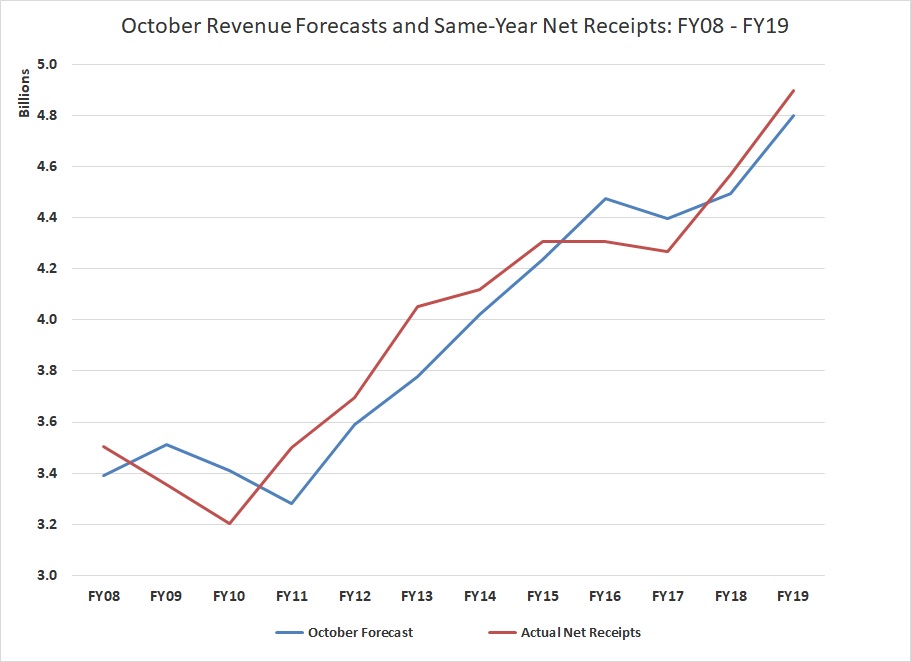

While the Nebraska Economic Forecasting Advisory Board recently increased its revenue projections for the current fiscal year by $161 million and for the next budget cycle by about $102 million,[1] it’s important to understand that the forecasting board’s projections are never spot on. The amount of money states take in fluctuates from year to year due to a variety of factors — many of which are out of a state’s control — including swings in personal income, slower consumer spending, federal tax and budget changes and unforeseen events like natural disasters. This natural volatility means that forecasting revenues is extremely difficult and it results in inaccurate forecasts year over year in Nebraska.

Over the past 12 years, October forecasts have differed from the year’s final receipts by more than $100 million eight times with revenues coming in below forecast in four of those years — by as much as $205 million.[2] (See chart above.) Projections for the following biennium, sometimes referred to as the “out years,” have been even more inaccurate. Actual year-end tax receipts in the state have differed from projections made in the prior fiscal year by more than $100 million in 10 out of the past 12 years, with revenues coming in below forecast in four of those years — by as much as $400 million — and above forecast in the other six.

This volatility isn’t unique to Nebraska: Pew Charitable Trusts has reported that state tax collections throughout the U.S. have become more volatile over the past decade.[3] As a result, Pew cautions against interpreting positive forecast upticks as a trend, which is what Nebraska would be doing if it based permanent policy changes on the recent forecast increases.

Forecast doesn’t account for possible recession

The Department of Revenue representative at the latest forecasting board meeting said the department’s increased revenue projections didn’t account for a potential recession. Many national economists, however, are predicting a recession as early as 2020.[4] If a recession does indeed strike, it would likely result in a considerable downturn in state revenues and cause actual tax receipts to come in significantly lower than projections. Should tax cuts or ongoing spending obligations have been enacted based on the recent projections, lawmakers would be forced to cut services or raise taxes or fees to balance the state budget.

One-time corporate income tax repatriation contributing to revenue upticks

Recent increases in corporate income tax revenue receipts and projections in Nebraska may be connected to corporations taking advantage of 2017 federal tax changes that allow them to claim offshore earnings at a reduced tax rate. Prior to the 2017 tax changes, corporations often stockpiled international earnings overseas to avoid paying the 35% tax rate the federal government applied to such income. But the 2017 changes have prompted many U.S. corporations to bring overseas income into the country. Offshore corporate earnings are now tax exempt once companies pay the initial repatriation tax rates of 15.5% on cash earnings and 8% on non-cash assets.[5] This means some of the current bump in corporate income tax revenue Nebraska is experiencing could be a one-time occurrence rather than being indicative of an ongoing increase in corporate income tax revenues.

Revenue surpluses better used to bolster Nebraska’s cash reserve

Bolstering the cash reserve fund is a more appropriate use of surplus revenues, especially during a period when states are experiencing significant revenue volatility. A strong cash reserve helps the state weather revenue ebbs and flows without making service cuts or tax changes in down years.

The $455.2 million in unobligated funds[6] currently in the cash reserve fund equate to only 9.3% of General Fund revenues.[7] The Legislative Fiscal Office recommends the cash reserve have balance of 16% of general fund revenues.[8] Even if the full $161 million projected surplus for FY20 materializes and is deposited in the cash reserve fund, it would only raise the balance to 12.1%. Similarly, if the projected FY21 surplus of $102 million becomes reality and goes into the cash reserve, it would take the balance to 13.9% of General Fund revenues. During the Great Recession, Nebraska spent $986 million — or almost 30% of General Fund revenues at the time — in federal stimulus, cash reserve and other one-time money to weather the downturn.[9] This spending was in addition to cuts to schools and other services. Nebraska is unlikely to receive stimulus funds the next time a recession hits, which makes having a strong cash reserve essential in protecting against tax and fee increases or cuts to real economy builders like schools, health care and public safety.

Ongoing expenditures need dedicated revenue to be sustainable

Every major study of Nebraska’s taxes since 1962, including the Legislature’s 2013 Tax Modernization Committee report,[10] has found that Nebraska relies heavily on property taxes to fund K-12 education and, repeatedly, the main recommendation to reduce this reliance has been to increase state support of Nebraska’s public schools. To do this sustainably, however, would require new revenue sources. Measures such as expanding the sales tax base to more consumer services, reforming some tax deductions and credits, increasing the state’s cigarette tax or enacting new taxes on high-income Nebraskans could help generate revenue to increase state support for K-12 and reduce our reliance on property taxes. Failing to find new revenue will undoubtedly force lawmakers to make cuts to vital services or increase other taxes and fees when revenues inevitably come in below projections at some point in the future.

Conclusion

Passing ongoing expenditures like tax cuts or new ongoing spending obligations based on projected future revenue increases, rather than identifying new revenue sources, is unsound fiscal policy that will have damaging consequences for our state. Conversely, putting surplus revenues in the state’s cash reserve should they actually materialize will leave Nebraska better prepared to handle the natural ups and downs of the economy.

Download a printable PDF of this analysis.