In school buildings across Nebraska this summer, it’s the budget builders and not the students who are doing the complex math. This month, the state provided final numbers on what K-12 districts will receive in state aid to factor into budgets for the 2023-2024 school year and how those dollars will figure into what each district can bring in through local property taxes.

The annual process to build a school district’s budget has some significant new calculations this year. The addition of foundation aid of $1,500 per student outlined in LB 583 contributed to a $110 million increase in funding to public education distributed through the state aid formula. LB 583 also increased reimbursement of special education costs to 80% for districts, which the Governor’s office estimates will provide an additional $199 million in school funding. Schools will factor this new funding for special education into their revenue estimates and budget planning but are not likely to receive these funds until sometime early next year.

To sustain the additional funding, the Legislature designated $1 billion for an Education Future Fund in LB 818 with the promise of ongoing annual contributions of $250 million. Linked to that significant investment is a 3% revenue cap included in LB 243 that school districts must comply with in the annual budget-setting process.

Of course, with 244 school districts varying from very large to very small and with very different student needs, the pieces of the puzzle of building a budget will fit together very differently.

Looking at the numbers

OpenSky ran the numbers for each of the districts, accounting for the new funding and the revenue cap in this analysis. Here are some of our findings:

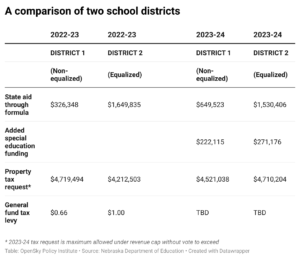

In neighboring school districts located in one of Nebraska’s rural counties, District 1 received more in state aid through the funding formula than a year ago, while District 2 gets less. As a result, District 1 is likely to lower what it requests in local property taxes next year. District 2 will likely require an increase.

What could be surprising to some is that the district requiring less in property taxes – a non-equalized district – already has a levy that is significantly lower than its neighbor, an equalized district with a levy already approaching the state-mandated lid. As a result, the gap in property taxes that landowners will pay on property of equal value across the two districts is likely to widen.

The state’s process of calculating the state aid formula this year also came with a surprise for districts, 38 of which (including District 2 illustrated above) learned that they will receive less in state aid through the formula than last year, even as overall funding paid out through the formula grew by 10%.

For most of the districts losing state aid, the loss in funding can be attributed to a recalculation of the poverty allowance, which is just one part of the state’s complex funding formula. When officials plugged in new numbers for students receiving free lunch, it altered each district’s “needs” calculation and all interrelated figures. Essentially, fewer students applying to receive free lunch during the COVID years (a time when federal funds were used to provide universal school meals in many districts) meant that many districts reported fewer students in poverty for the purposes of the state aid formula and that led to unexpected shifts in state aid.

As you would expect, districts receiving equalization aid were hardest hit by the adjustment, accounting for 33 of the 38 districts that saw their state aid paid out through the formula drop from last year.

Exploring the finance formula

The change in the poverty allowance, while not part of any new legislation, exemplifies the volatility of the formula in which adjustments to one calculation can have a ripple effect elsewhere, with districts ultimately ending up as winners or losers in state aid. And within this complicated series of calculations, the addition of the revenue cap strips school districts of their flexibility in responding when costs increase and state aid provides fewer dollars than expected.

This year’s additional investment in education as spearheaded by the Governor represents a big step forward in how Nebraska funds public education. A next step should be a thorough study of the school finance formula to more accurately address needs and outcomes for Nebraska’s students.