Policy brief: Higher property taxes for most if Nebraska lowers agricultural land valuations

Taxing agricultural land at only 65 percent of its full market value – which is proposed in several bills currently before the legislature[1] — would likely lead to service cuts or higher property taxes for the vast majority of Nebraskans.

Tax increases or cuts to services like K-12 schools, community colleges, roads and law enforcement would be needed to offset the loss of $102.5 million in revenue for these local entities if lawmakers cut the valuation of agricultural land from its current 75 percent of full market value.

How Nebraska values property

Agricultural land in Nebraska has been taxed at less than full market value since 1992 and is currently taxed at 75 percent of its market value.[2] In contrast, business and residential property is taxed at 100 percent of market value. The average property tax levy on agricultural land in 2012 was $1.17 per $100 of market value, compared to a statewide average of $2.09 per $100 for residential real property.[3]

Reliance on agricultural property taxes increasing

Despite assessing agricultural land at a lower rate for taxes, localities like counties and school districts rely more and more on revenue from these taxes. The state’s agricultural economy experienced a boom over the past decade, and the average inflation-adjusted value of an acre of farmland more than doubled from 2007 to 2012, reaching an all-time high.[4] As a result, Nebraska now relies on agricultural land for 29 percent of all property tax revenue, up from 24 percent in 2002.

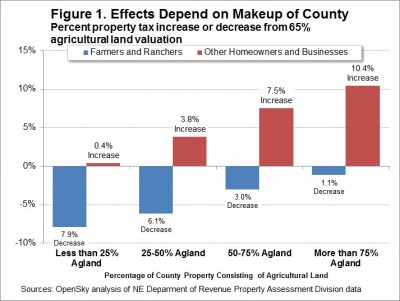

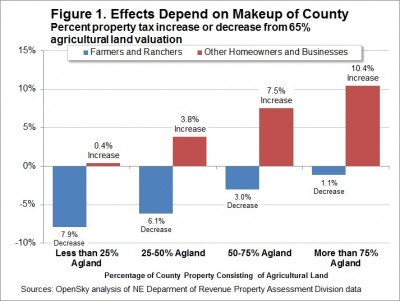

Most agricultural parts of the state would see little benefit

While it would naturally seem intended to help the agricultural community, the largest benefits would not go to the most rural parts of Nebraska, but rather to farmers and ranchers near urban areas. This is because the property tax revenue lost from farmers and ranchers near urban areas can be made up with higher property taxes on business and residential property owners in those areas. Such tax shifts can’t occur to the same extent in more rural areas where there are not as many businesses and residential property owners. This means those communities must make up the lost revenue either by levy increases – which would wipe out much of the tax cut from lowering valuation – or by cuts to education, roads and other local services.

Big revenue losses at the local level

The $102.5 million shortfall that would hit Nebraska’s localities would include $68.2 million for K-12 schools, $21.9 million for counties and $6.2 million for community colleges. Current law would call for $29.5 million more in state school aid,[5] but that funding is not guaranteed and would not be triggered until the second year after valuations were decreased.[6]

School aid increase would not cover losses

Even if the state funds the school aid increase, it would cover less than half of K-12 schools’ lost revenues and counties, community colleges and other local entities would not be helped at all. To avoid service cuts, property tax levy rates across the state would have to increase an average of 4.5 cents, and at least 14 counties[7] would be pushed over their levy limits.

If school aid is not increased

To avoid service cuts if the state does not fund the school aid increase:

- All residential and commercial property owners would see tax increases (Fig. 1);

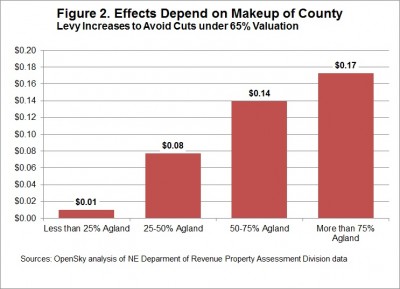

- Levies across the state would have to increase an average of 6.3 cents, including 17.3 cents in the most agricultural parts of the state (Fig. 2 next page); and

- More than 100 school districts would be pushed over their levy limits.

Problems would grow if agricultural land values drop

This analysis is based on the most recent property tax data available, 2012,[8] showing the revenue losses and property tax shifts that would occur due to a 65 percent agricultural land valuation, all other things being equal.

These revenue losses would get worse if future land values fall on their own from current historically high levels. Residential and business property owners would have to pay even higher property taxes or local officials would have to make deeper service cuts to recover the bigger shortfall.

Conversely, a continued rapid climb in agricultural land prices may temporarily mask some of the budget shortfalls and property tax shifts caused by the valuation change.

Decreasing valuations for school-aid worth looking at

There is merit, however, in the idea of reducing agricultural land value for state school aid purposes only. Such a measure would increase the number of schools that qualify for state equalization aid, helping those school districts that have fallen out of equalization in recent years due to rising agricultural land values.

Based on FY 12-13 data,[9] the change would have brought 21 school districts back into equalization and unlike the Property Tax Credit program, it would target the aid to areas with relatively high tax levies. The data also show 160 districts would benefit, 152 of which had levies of at least 95 cents. All 160 of these districts had levies of at least 80 cents.

This measure also would target aid to districts with agricultural land without shifting taxes onto other homeowners and businesses in those areas, as would happen if agricultural land values were dropped for all taxing purposes. If land valuation was decreased for school-aid purposes only, all property tax payers in the affected districts would benefit from any reduction in property taxes, and it would not cause schools to increase their levy rates and potentially run into the $1.05 levy limits. Furthermore, such a measure would not result in a loss of revenue for schools, community colleges, counties and other local governments.

Other options for addressing property taxes

It’s vital that lawmakers lower property taxes, a sentiment expressed by hundreds of Nebraskans this fall at public hearings of the Tax Modernization Committee. Reducing agricultural land valuations, however, would increase – not lower — property taxes for most residents.

As we note above, decreasing agricultural land values for school-aid purposes is an option that might be better suited for Nebraska. Other approaches lowering property taxes to consider include:

- Increasing state aid to schools, community colleges, counties, cities and other localities to reduce their reliance on property taxes to fund services;

- Having the state take over programs that it requires at the local level to lower costs for localities;

- Using “circuit breakers” that provide targeted property tax assistance to farmers, ranchers and others who pay high property taxes in relation to their incomes; and

- Expanding the Homestead Exemption – a property tax relief program for seniors, certain disabled people and totally disabled veterans — to reach more taxpayers.

Download a printable PDF of this analysis.

[1] Including LB 670, LB 721, and LB 813.

[2] http://www.legislature.ne.gov/app_rev/source/narrative_proptaxhistory.htm. Agricultural land valuation was dropped to 75 percent from 80 percent in 2006.

[3] All property tax statistics are OpenSky analysis of NE Department of Revenue Property Assessment Division, Certificate of Taxes Levied data.

[4] University of Nebraska-Lincoln Department of Agricultural Economics, “Nebraska Farm Real Estate Market Highlights 2012-2013.”

[5] OpenSky analysis of NE Department of Revenue Property Assessment Division, Certificate of Taxes Levied data. See also LB 145 Fiscal Note, February 2013.

[6] State aid to K-12 schools is determined using data from the most recent prior year, so any aid increase resulting from lower agricultural land valuations would not materialize until the second year of the change.

[7] The following counties would have had to exceed their 50 cent levy limit to raise the same amount of money on their reduced property tax base in 2012: Burt, Cass, Franklin, Garden, Holt, Johnson, Logan, Loup, Madison, McPherson, Nance, Scotts Bluff, Sherman, and Thurston.

[8] NE Department of Revenue Property Assessment Division, Certificate of Taxes Levied data. The most recent year available for full analysis at the time of writing is for 2012.

[9] OpenSky Analysis of state aid calculation for 2012-2013 from NE Department of Education and property tax data from NE Department of Revenue Property Assessment Division.